How are you handling Promise Debt?

by Henrik Holen on Mon Oct 06 2025

In the kickoff workshop for my startup’s first large enterprise contract, there were twenty-five people from the customer. They had all showed up to align on the work and lay the groundwork for this new product launch. We were seven people in our entire company.

We’d spent six months of contract reviews, endless meetings, and way too much money on lawyers, to win this massive deal. We had outcompeted companies 100x our size, checked every box, and cleared every procurement hurdle, and we were justifiably proud of ourselves. Once we got past this stage with our previous customers, it was a pretty smooth ride. Things kind of just worked itself out.

“Working itself out” isn’t really how giant, multi-national corporations do things. Enterprises are built to eliminate risk. Startups are built for it. They can just change course when they learn something new. Large corporations don’t work that way. Instead, they plan, lock things down, and remove surprises. They love the idea of working with someone who moves fast, but that speed is risky, and the natural response is a contract that tries to contain it.

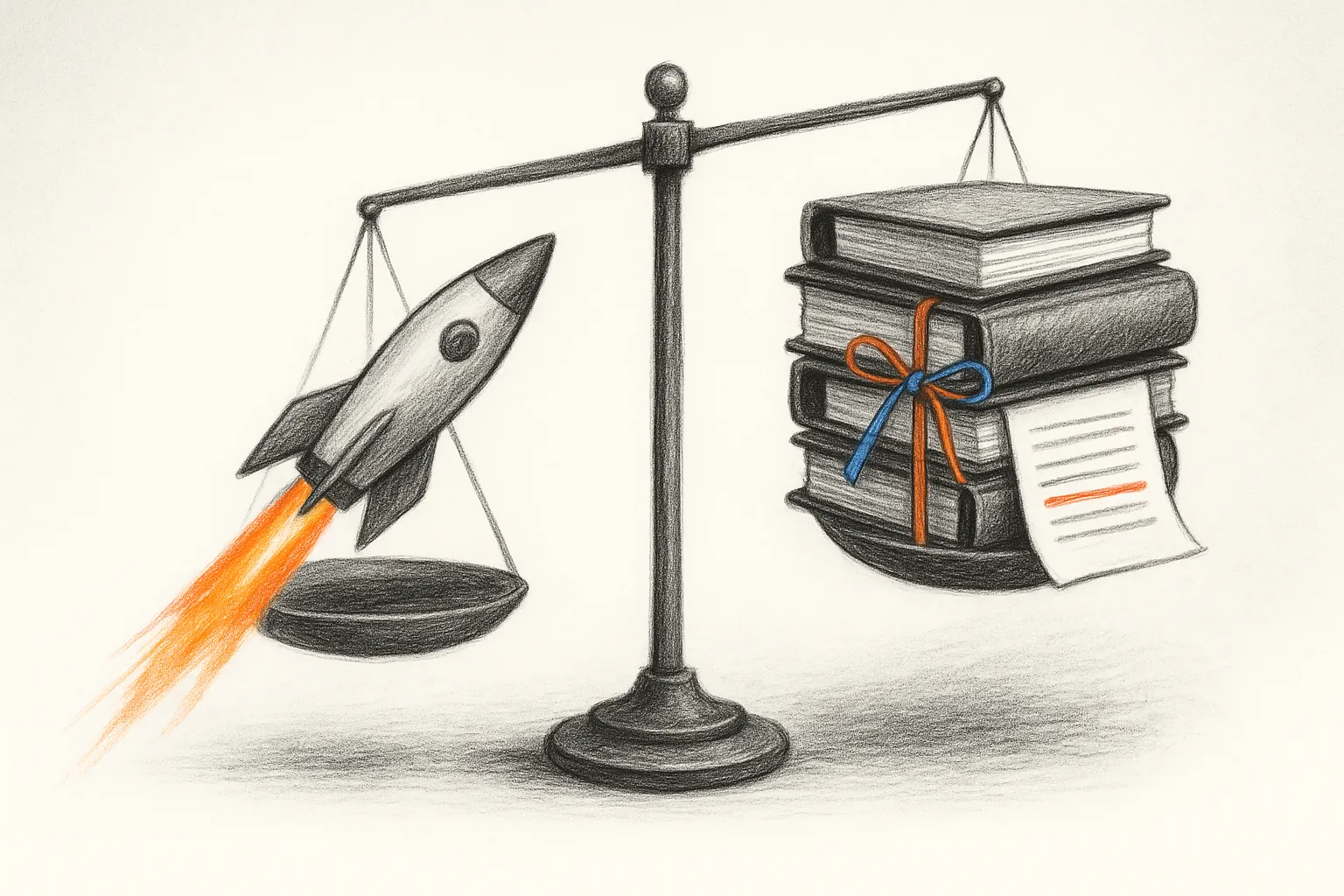

That meant that we had accrued a bunch of unintentional commitments. The small agreements that we had made in passing or an idea that got shared in a meeting turned into contract clauses, which turned into Jira tickets, and started affecting our roadmap. You’re familiar with technical debt. You can call this promise debt.

In the early stages of a deal, the lawyers get busy with the usual things like liability caps, payment terms and support hours. Those are the parts that are measurably risky, so both sides argue over them, sometimes for weeks. Everyone takes them seriously, because they’re easy to quantify and defend.

The product often doesn’t get that treatment. That’s where you, the product owner or founder, are left to your own devices. You get to dream alongside your customer, talk about what you’re building, and promise things that already sound close to your plan. Unfortunately, the exciting brainstorm over lunch becomes something your team is contractually expected to ship.

That’s why you have to assume the contract will be treated as roadmap. Which means reading every feature-related line with the same care as liability clauses. Ask whether you’ll still want to do it six months from now. Once written down, it starts to impact your product development. A convenience feature or internal tool you thought was optional becomes non-negotiable. Timelines shift. Priorities get reordered. Items that weren’t really on the roadmap two weeks ago now have hard deadlines.

Promise debt doesn’t just weigh on your roadmap, it weighs on your team. Instead of asking what to build next, you start asking what’s left to deliver. It changes what it means to work on the product. Before long, you’re trying to align multiple customers on features that don’t quite align with each other.

That is why a clear vision is so important. You need to communicate your vision clearly and make sure your customer buys into it. If you share a view of what the world should look like, at least you’ll be on the same wave length when the requests start coming in. This is so important that it might be worth walking away from customers who have a very different approach.

In enterprise sales, the leverage isn’t equal. Customers set the tempo and they have the budget. You want the deal. Which means, sooner or later, you’ll agree to something you didn’t plan to close. It can be a discount or it can be some new developments. That doesn’t have to mean giving up control.

A key approach is to commit to outcomes instead of features. By framing the conversation around the problem, not the implementation, you can get the space to build in a way that fits your product and aligns better with your roadmap.

In addition, you can dedicate a portion of your quarterly development capacity to customer-driven initiatives. For this to work, you’ll need to get buy-in from all your customers (which likely won’t be easy). They can all submit requests, which you prioritize based on impact and feasibility, so the most valuable requests get delivered first.

Finally, adding a price will separate the nice to have from the need to have. If they insist on a development during the contract process or insist on delivery of a specific request, it can be scoped as a billable project outside of the shared capacity. By committing to do work, but adding a cost to that development, you increase the tension around actually calling for the job to be done. It’ll only be requested if it is considered valuable, and worth the budget allocation.

Sometimes you won’t get that luxury though. You’ll have no choice but to build something specific for free. When that happens, do your best to make it your own. The closer you get it to your own vision, the easier it’ll be to maintain in the long term.

Ultimately, You will accrue promise debt. There is no way around it. But if customers trust your vision, they’ll be less likely to try to define it for you. They’ll want to be part of creating this new world, but you’ll in the driver’s seat, with only the occasional backseat driving.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Get my latest thoughts on product and strategy delivered to your inbox.